As ever, it's been a busy start to the new term, with a well attended chilli night at the Stables followed by very successful Freshers' Weekend at the Hut on Mendip and, at the time this is being written, a second Freshers' Weekend in South Wales!

Student membership now stands at over 50 (possibly a record for this early in the year!), getting the 2025/26 caving season off - or rather under - the ground in style.

So, a very warm welcome to all our new and returning members!

The newsletter is the main way we record what goes on for in the club, and the production of newsletters goes back right to the start of the Society in 1919! All our newsletters have been scanned and you can find our printed newsletters on our website along with a full archive of our online ones, which started in 2019. So take a trip back in time to any year you fancy visiting and see what was going on.

Our student editor, BIlly Evans, is stepping down now to concentrate on his final year, so we're looking for a new recruit to join the editorial team. As you'll see, we've got a wide variety of contributors, so you don't have to write the content yourself. The newsletter is put together and distributed via Mailchimp, and Linda is happy to continue with that side of things. The main thing we need is a student editor who's keen to get involved and happy to help keep the content coming! If you're interested, please let us know. We'd love to have to on board!

And Linda would like to take this opportunity to thank Billy, on behalf of all of us, for everything he's done over the past couple of years!

Student membership now stands at over 50 (possibly a record for this early in the year!), getting the 2025/26 caving season off - or rather under - the ground in style.

So, a very warm welcome to all our new and returning members!

The newsletter is the main way we record what goes on for in the club, and the production of newsletters goes back right to the start of the Society in 1919! All our newsletters have been scanned and you can find our printed newsletters on our website along with a full archive of our online ones, which started in 2019. So take a trip back in time to any year you fancy visiting and see what was going on.

Our student editor, BIlly Evans, is stepping down now to concentrate on his final year, so we're looking for a new recruit to join the editorial team. As you'll see, we've got a wide variety of contributors, so you don't have to write the content yourself. The newsletter is put together and distributed via Mailchimp, and Linda is happy to continue with that side of things. The main thing we need is a student editor who's keen to get involved and happy to help keep the content coming! If you're interested, please let us know. We'd love to have to on board!

And Linda would like to take this opportunity to thank Billy, on behalf of all of us, for everything he's done over the past couple of years!

Linda and Billy

PS, as ever, if the text is blue and underlined it means it's a clickable link.

In this issue:

- EGM notice and meeting link

- Farewell to Struan Robertson

- The Ballad of Doolin Cave

- Let There Be Light

- Dry as a Bat's Bath

- A Note on Names

- Tidy, Thank You, Liz!

- Museum News

- Digging Night at Gibbett's Brow

- The Wait for Cheddar is Nearly Over!

- Into the Hell Hole

- A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

- Scrotum Clampers and Wild Heads

- Rita Rhino Read to the End, Did You?

- EGM notice and meeting link

- Farewell to Struan Robertson

- The Ballad of Doolin Cave

- Let There Be Light

- Dry as a Bat's Bath

- A Note on Names

- Tidy, Thank You, Liz!

- Museum News

- Digging Night at Gibbett's Brow

- The Wait for Cheddar is Nearly Over!

- Into the Hell Hole

- A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

- Scrotum Clampers and Wild Heads

- Rita Rhino Read to the End, Did You?

UBSS EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING

19 NOVEMBER 2025

8PM BY ZOOM

19 NOVEMBER 2025

8PM BY ZOOM

As a report in the July edition of our newsletter explained, changes brought in by the Students' Union over summer mean that our membership structure can no longer be supported by them and, after much brainstorming and discussion, a plan was hatched that we hope will satisfy everyone and mean that UBSS can look forward with confidence to its next 100 years.

The proposal that will at some point (next year, we hope) come to the society as a whole for approval at an AGM or EGM is that we should apply for formal charitable status and become a Charitable Incorporated Organisation (CIO) under the aegis of the Charities Commission. This suggestion met with the approval in a meeting held in July with the University represented by John McWilliams (Director of Civic and Alumni Engagement) and Ben Pilling (SU CEO) with Linda Wilson and David Richards from UBSS. Following this, Graham Mullan and Elliott McCall with assistance from others, have been working on a draft constitution and the working draft can be found by following this link. Incorporation will have considerable benefits, including but not limited to, the removal of personal liability from officers and members. The majority of large clubs have now achieved or are seeking incorporation in one form or another, so we are by no means alone in making this sort of change. Incorporation will also provide us with a suitable governance structure for Arts Council Accreditation if we are able to achieve that for the museum.

To give the membership as a whole the opportunity to discuss this and ask any questions, the committee has called an EGM to be held by Zoom at 8pm on 19 November 2025. We hope as many of you as possible will take the time to come along to discuss these proposed changes.

This draft is still a work in process. We believe/hope that this will be approved by both the Charities Commission and the Arts Council, but there will no doubt be some changes needed along the way.

This meeting will be held over zoom and this is the link:

https://bristol-ac-uk.zoom.us/j/91447517844

Meeting ID: 914 4751 7844

It is unlikely that this process will be completed early enough next year for a new constitution and formal transfer to the new body to be adopted at the AGM, in which case a further EGM will be needed. But in the meantime, save the date for the AGM (and annual dinner) anyway, March 14th 2026!

Please come along to the EGM so the committee knows that these proposed changes have the approval of the wider membership!

FAREWELL TO STRUAN ROBERTSON

Struan on the Alderney cliffs. Photo by Sandy Robertson.

Those who knew him will be saddened to hear of the death of D.A.S. ‘Struan’ Robertson at the age of 93, earlier this month. Struan was UBSS Secretary (twice) in the 1950s and was one of the original explorers of the Doolin River Cave. A full obituary will appear in the forthcoming issue of our Proceedings.

Struan composed the Ballad of Doolin Cave and also coined the term spelaeodendron for the type of willow tree (salix caprea) that often marks the entrance to a Co Clare cave.

The ballad recalls when, in the early days of Society’s trips to Co. Clare, Fisherstreet Pothole seemed like an obvious place to explore. It had been descended in 1936, but that exploration had been halted by the extremely ripe dead cow festering at the bottom of the pitch.

In the early 1950s, the pot was deemed to be not much of a lead as it was 12m deep and only 23m above sea level. So it was felt there was unlikely to be much open passage downstream and that any upstream route would also be barred after a short distance as it would have to pass under the River Aille where this was running on limestone.

However, when it was descended again, shortly after the first exploration of the upstream swallet, St. Catherine’s, the first rough survey did show open cave passage passing under the river. Not only that, but the end of the survey was very close to the downstream end of the St. Catherine’s survey.

So, the moral of the story is: never presume – explore instead!

Struan’s son, Sandy, would be delighted to hear from anyone with tales of his father’s caving days, so if you do remember Struan, Sandy can be contacted via me.

Struan on the Alderney cliffs. Photo by Sandy Robertson.

Those who knew him will be saddened to hear of the death of D.A.S. ‘Struan’ Robertson at the age of 93, earlier this month. Struan was UBSS Secretary (twice) in the 1950s and was one of the original explorers of the Doolin River Cave. A full obituary will appear in the forthcoming issue of our Proceedings.

Struan composed the Ballad of Doolin Cave and also coined the term spelaeodendron for the type of willow tree (salix caprea) that often marks the entrance to a Co Clare cave.

The ballad recalls when, in the early days of Society’s trips to Co. Clare, Fisherstreet Pothole seemed like an obvious place to explore. It had been descended in 1936, but that exploration had been halted by the extremely ripe dead cow festering at the bottom of the pitch.

In the early 1950s, the pot was deemed to be not much of a lead as it was 12m deep and only 23m above sea level. So it was felt there was unlikely to be much open passage downstream and that any upstream route would also be barred after a short distance as it would have to pass under the River Aille where this was running on limestone.

However, when it was descended again, shortly after the first exploration of the upstream swallet, St. Catherine’s, the first rough survey did show open cave passage passing under the river. Not only that, but the end of the survey was very close to the downstream end of the St. Catherine’s survey.

So, the moral of the story is: never presume – explore instead!

Struan’s son, Sandy, would be delighted to hear from anyone with tales of his father’s caving days, so if you do remember Struan, Sandy can be contacted via me.

Graham Mullan

THE BALLAD OF DOOLIN CAVE

Now Spelaeos listen to me,

Away down Doolin,

And I'll sing you a song of a cave near the sea,

'Way down at the Doolin strand.

Then away, theories, away; away down Doolin,

For the spelaeodendron,

It grows with its end on

The Pothole to Doolin Cave.

Now theories are all very well,

Away from Doolin,

But when you get there you must send them to hell

'Way down in the Doolin Cave.

Then away, theories, away; away from Doolin,

No bedding planes flooded

Though we get all muddied

While down in the Doolin Cave.

The river that's known as the Aille

Adown near Doolin

It's this we go under, oh, ever so dryly

Way down in the Doolin Cave.

So 'way theories away; away from Doolin,

Exploded are theories

Except where the beer is

Kept down at O'Lafferty's bar.

Struan Robertson

LET THERE BE LIGHT!

Some of the fruits of Dan's labours. Photo by Graham Mullan.

Student President Dan Rose has recently boosted the club's resources by gaining valuable sponsorship from two companies. Dan describes this success ...

Universally, the collective teeth of the club’s current student body were cut on two LED lamp manufacturers – Fenix and Sofirn. Spearheading the ‘Chinesium Revolution’, these two companies have in recent years provided low cost, high-quality lights to student cavers wishing to experience the superiority of lithium iron 18650/21700 batteries without decimating their student loans on Scurions/Rude Noras (as wonderful as those lights apparently are).

Lighting up the night using the Fenix LR35R pro. Left, with no extra light, right, with Fenix LR35.

Hence, since joining UBSS, I’ve had an intimate affection for these companies, viewing them as social goods; the kind of products that would make Adam Smith’s eyes gleam at the beauty of the market’s invisible hand, and would surely cause Marx to question his conclusions.

Yet, as any astute student is aware – free goods are always better than those that are paid for. Thus, over the summer, I switched my studies from history to marketing, and took on the role of UBSS brand ambassador, sending out carefully worded, sycophantic spam to two companies that, although in market competition, collude in the caving world in the most wonderful of coalitions. ‘Dear Fenix and Sofirn marketing, UBSS is a deeply historic club with a media output capable of turning heads and disrupting markets… collaborate with us, and allow our success, to be your success’. Back and forths were had, negotiations made, and through our many textual convenings, two sponsorships emerged, floating from the depths of discussion like the foam atop a Guinness.

Both firms needed convincing, but thanks to an MCCBTV video here, an UBSS trip writeup there, they soon came around to the idea that a mutually beneficial relationship should be pursued. In the end I managed to secure 15 free new lights for UBSS – ten from Sofirn, and five from Fenix, on the promise that we would photograph ourselves using them and send them back to them for advertising. Included in this were many standard head torches (including a few of the Sofirn HS20s I reviewed a couple newsletters back), as well as a number of more expensive, high-tech search lights, including the Fenix HP35R; a headtorch that can reach up to 4000 lumens, and the terrifyingly bright, cave-melting Fenix LR35R Pro, a handheld searchlight that can reach an eye-blinding 10,000 lumens! Ideal for backlighting photography, or searching for a black cat on a dark, misty Mendip night. Overall, about £1,100 of free gear!  Sponsorship photos: Left, Joshitha Sivakumar and Emily Wormleighton in Fairy Cave Quarry, photo by Jess Brock and right, Mowgli Palmer at Bull Pot of the Witches, photo by Joshitha Sivakumar.

Sponsorship photos: Left, Joshitha Sivakumar and Emily Wormleighton in Fairy Cave Quarry, photo by Jess Brock and right, Mowgli Palmer at Bull Pot of the Witches, photo by Joshitha Sivakumar.

Now, the next stage: preservation and creation. These lights must not be lost! They were free but they are valuable, cherish them as though you paid for them yourself. They are immensely useful and it would be tragic to tell Sofirn and Fenix that we don’t have any pictures of us using them because we lost them in the first term of the year.

This is preservation. Creation, meanwhile, is our positive task. Use the lights, take wonderful pictures of you using them, and send them to me (my contact details are under this article). Both companies have loved the photos I’ve already sent them and the more we send the more free stuff they’re likely to send. There is no reason that this should be a one-off perk! The honey-moon phase of our relationship is in full swing; let’s cherish and tend to it, and cement it as a long-term marriage. So, take photos and send them to me! Just as God said: let there be (free) light.

Please send photos to me of you using the free lights.

Some of the fruits of Dan's labours. Photo by Graham Mullan.

Student President Dan Rose has recently boosted the club's resources by gaining valuable sponsorship from two companies. Dan describes this success ...

Universally, the collective teeth of the club’s current student body were cut on two LED lamp manufacturers – Fenix and Sofirn. Spearheading the ‘Chinesium Revolution’, these two companies have in recent years provided low cost, high-quality lights to student cavers wishing to experience the superiority of lithium iron 18650/21700 batteries without decimating their student loans on Scurions/Rude Noras (as wonderful as those lights apparently are).

Lighting up the night using the Fenix LR35R pro. Left, with no extra light, right, with Fenix LR35.

Hence, since joining UBSS, I’ve had an intimate affection for these companies, viewing them as social goods; the kind of products that would make Adam Smith’s eyes gleam at the beauty of the market’s invisible hand, and would surely cause Marx to question his conclusions.

Yet, as any astute student is aware – free goods are always better than those that are paid for. Thus, over the summer, I switched my studies from history to marketing, and took on the role of UBSS brand ambassador, sending out carefully worded, sycophantic spam to two companies that, although in market competition, collude in the caving world in the most wonderful of coalitions. ‘Dear Fenix and Sofirn marketing, UBSS is a deeply historic club with a media output capable of turning heads and disrupting markets… collaborate with us, and allow our success, to be your success’. Back and forths were had, negotiations made, and through our many textual convenings, two sponsorships emerged, floating from the depths of discussion like the foam atop a Guinness.

Both firms needed convincing, but thanks to an MCCBTV video here, an UBSS trip writeup there, they soon came around to the idea that a mutually beneficial relationship should be pursued. In the end I managed to secure 15 free new lights for UBSS – ten from Sofirn, and five from Fenix, on the promise that we would photograph ourselves using them and send them back to them for advertising. Included in this were many standard head torches (including a few of the Sofirn HS20s I reviewed a couple newsletters back), as well as a number of more expensive, high-tech search lights, including the Fenix HP35R; a headtorch that can reach up to 4000 lumens, and the terrifyingly bright, cave-melting Fenix LR35R Pro, a handheld searchlight that can reach an eye-blinding 10,000 lumens! Ideal for backlighting photography, or searching for a black cat on a dark, misty Mendip night. Overall, about £1,100 of free gear!

Now, the next stage: preservation and creation. These lights must not be lost! They were free but they are valuable, cherish them as though you paid for them yourself. They are immensely useful and it would be tragic to tell Sofirn and Fenix that we don’t have any pictures of us using them because we lost them in the first term of the year.

This is preservation. Creation, meanwhile, is our positive task. Use the lights, take wonderful pictures of you using them, and send them to me (my contact details are under this article). Both companies have loved the photos I’ve already sent them and the more we send the more free stuff they’re likely to send. There is no reason that this should be a one-off perk! The honey-moon phase of our relationship is in full swing; let’s cherish and tend to it, and cement it as a long-term marriage. So, take photos and send them to me! Just as God said: let there be (free) light.

Please send photos to me of you using the free lights.

Dan Rose

DRY AS A BAT'S BATH

Where's all the water gone? Swildon's entrance. Photo by Stuart Alldred.

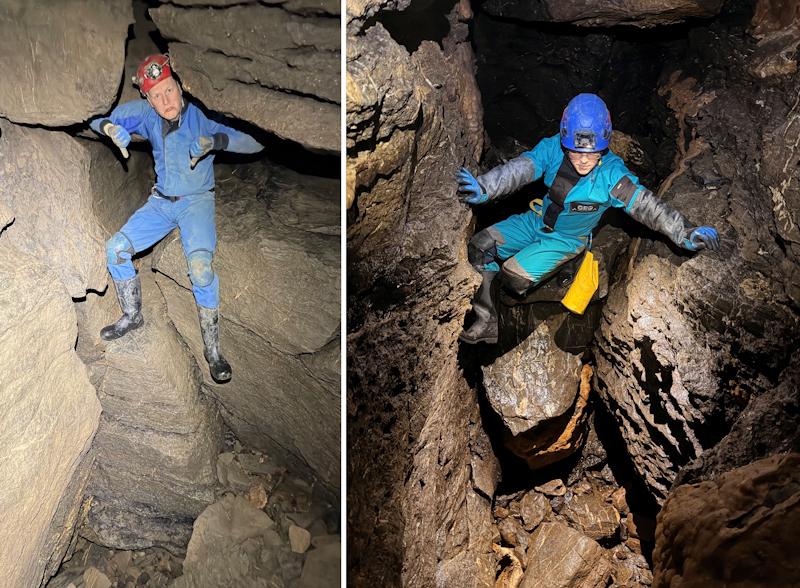

After taking some new recruits into Swildons entrance series on Fresher’s weekend and discovering it to be incredibly dry, Stuart Alldred was keen to carry on down the ladder and explore further. So two days later, he and Mike Waterworth set off to do the Short Round. Stuart describes what they found …

The stream that normally flows into the entrance had completely dried up, and as we followed the Short Dry Way in, only a few stranded puddles remained. Mike managed to reach the ladder without even a damp patch. I, however, had had a suspicion that my neofleece would still be required further on, so had made the necessary decision to sit in the (now half filled) ‘bath’ so I didn’t overheat.

Still searching ... left, Stuart Alldred, right, Mike Waterworth.

A small amount of water joined us at the bottom of the 40’ climb which made the descent down the ladder a bit damp. From there we followed the route previously known as the streamway until we reached the climb up into Tratman’s Temple. Along the way, the Twin Pots still provided me with the customary fun of jumping in, unlike Mike who did his best to stay dry. By that point, I’d decided it was more of a challenge to stay wet.

Whilst wandering past Shatter Series and towards the Greasy Chimney, Mike had a play with the LiDAR on his phone, seeing how it would cope with mapping the cave at walking speed. (If you’d like to see another cave that he has been mapping with his phone, he has made a video about the progress made in White Rabbit.

The Short Round wasn’t too different to when I last passed through in April with Clive. The Troubles were still passable on our stomachs and required no bailing. Although the first duck was notably lower - I almost missed the times I had to sit around waiting for the siphon to do its job, then carefully floating through sans helmet with just my nose sticking above water. Almost!

Left, Mike Waterworth, still looking for water and right, Stuart Alldred on the 20' Pitch, celebrating the success of their quest.

After hurtling down the slide at a mildly reckless speed, I was intrigued as to how low Sump 2 was. I set off to investigate while Mike remained behind but halfway through the pebbly hands-and-knees crawl, I realised I really couldn’t be arsed and turned around to rejoin him. We found Sump 1 was technically a duck, although only by a few centimetres and definitely not one you’d want to float through on your back. From there, we made quick progress back to the entrance, leaving any trace of water behind at the ladder.

I’ve since heard that Mud Sump has now re-sumped, so it’s likely the Short Round will remain closed now until next year. (Unless there are some particularly keen people who want to sit there for hours bailing). For anyone who has yet to do the trip, it’s one of my favourites on Mendip and highly recommended when it re-opens.

Where's all the water gone? Swildon's entrance. Photo by Stuart Alldred.

After taking some new recruits into Swildons entrance series on Fresher’s weekend and discovering it to be incredibly dry, Stuart Alldred was keen to carry on down the ladder and explore further. So two days later, he and Mike Waterworth set off to do the Short Round. Stuart describes what they found …

The stream that normally flows into the entrance had completely dried up, and as we followed the Short Dry Way in, only a few stranded puddles remained. Mike managed to reach the ladder without even a damp patch. I, however, had had a suspicion that my neofleece would still be required further on, so had made the necessary decision to sit in the (now half filled) ‘bath’ so I didn’t overheat.

Still searching ... left, Stuart Alldred, right, Mike Waterworth.

A small amount of water joined us at the bottom of the 40’ climb which made the descent down the ladder a bit damp. From there we followed the route previously known as the streamway until we reached the climb up into Tratman’s Temple. Along the way, the Twin Pots still provided me with the customary fun of jumping in, unlike Mike who did his best to stay dry. By that point, I’d decided it was more of a challenge to stay wet.

Whilst wandering past Shatter Series and towards the Greasy Chimney, Mike had a play with the LiDAR on his phone, seeing how it would cope with mapping the cave at walking speed. (If you’d like to see another cave that he has been mapping with his phone, he has made a video about the progress made in White Rabbit.

The Short Round wasn’t too different to when I last passed through in April with Clive. The Troubles were still passable on our stomachs and required no bailing. Although the first duck was notably lower - I almost missed the times I had to sit around waiting for the siphon to do its job, then carefully floating through sans helmet with just my nose sticking above water. Almost!

Left, Mike Waterworth, still looking for water and right, Stuart Alldred on the 20' Pitch, celebrating the success of their quest.

After hurtling down the slide at a mildly reckless speed, I was intrigued as to how low Sump 2 was. I set off to investigate while Mike remained behind but halfway through the pebbly hands-and-knees crawl, I realised I really couldn’t be arsed and turned around to rejoin him. We found Sump 1 was technically a duck, although only by a few centimetres and definitely not one you’d want to float through on your back. From there, we made quick progress back to the entrance, leaving any trace of water behind at the ladder.

I’ve since heard that Mud Sump has now re-sumped, so it’s likely the Short Round will remain closed now until next year. (Unless there are some particularly keen people who want to sit there for hours bailing). For anyone who has yet to do the trip, it’s one of my favourites on Mendip and highly recommended when it re-opens.

Stuart Alldred

A NOTE ON NAMES

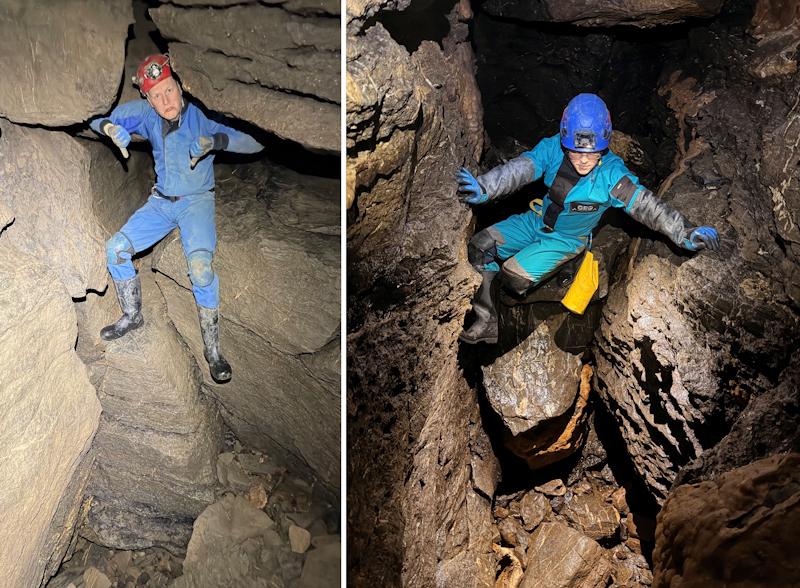

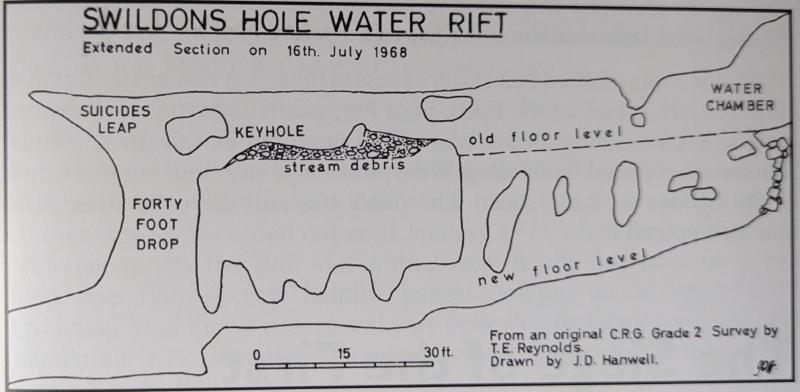

Diagram of the Water Rift after the Great Flood of 10th July 1968.

New cavers often wonder why a 3m climb is sometimes still referred to as the ‘Forty’ and a 6m ladder pitch is called the ‘Twenty’. Graham Mullan gives a brief explaination of two of the the puzzling names in Swildon's Hole.

The origin of the ‘Twenty’ is the easiest question to answer. It's roughly 20 feet deep, although in the interests of strict accuracy, it’s actually a bit shorter than that, but 20 is a nice round number and so the name stuck. It was first reached in 1914 but not passed until July 1921, seven years later.

The reason that the descent of the Twenty took so long was that there was a far more formidable obstacle further upstream - the ‘Forty’. Twice the depth and, for most of the time very, very wet. It’s difficult to appreciate now, but back in the early years of the 20th century the cave was much wetter and without modern caving gear exploaration presented a much more difficult challenge.

The problem of water was much reduced in the 1950s when the water company began abstracting from a source upstream of the entrance. Other factors, including changing weather patterns, have also contributed, to say nothing of the vast improvements in equipment and in clothing since the 1920s.

To see the Twenty as it is now, look at the photo on the right in the pair above in Stuart's trip write up. And for the now inaptly names Forty, look at the photo on the left with the caver standing only a few metres about floor level and read on to discover how it came to be like this ...

The ‘Forty’ was first reached in the 1900s. The approach to it is the Water Rift which in those days was tight, nasty and very wet. This ended in the Keyhole and climbing above that to ‘Suicides’ Leap’ enabled the impressive shaft to be reached. This was a serious obstacle and wasn’t successfully descended until August 1914, when the Twenty was first reached.

The Keyhole was widened quite soon after discovery and gave much easier access to the head of the pitch. This was a short distance below Suicides’ Leap and is the reason why the ‘Forty’ was only 35’!

As well as the weather, the minor matter of the First World War kept cavers somewhat preoccupied, and it wasn’t until the drought in the summer of 1921 that it was successfully passed once more and the Twenty passed for the first time.

More downstream exploration followed, but the Forty remained a serious obstacle and various attempts, some more successful than others, were made to divert the water away from people on the ladder. All this effort was rendered unnecessary in July 1968 when the Great Flood (a serious event, about which books have been written and TV documentaries made) completely altered the place. The bottom of the Water Rift had simply been filled with silt and sediment, held in place by a blockage near the bottom of the pitch. This was blasted out by the force of water leaving the gentle descent to the short climb down that we have today.

So when you next drop down through the hole at the bottom of the Water Rift and land in a tall, round chamber, look up and imagine what it would have been like climbing down a rope ladder wearing a tweed jacket and cap over ordinary trousers with nothing more than a candle to light your descent. Then imagine water pouring on your head at the same time and you might have some idea how the original explorers might have felt.

All this and much more can be found in the book 'Swildon’s Hole 100 years of Exploration' by Dave Irwin, Ali Moody and Andy Farrant.

TIDY, THANK YOU, LIZ!!

Diagram of the Water Rift after the Great Flood of 10th July 1968.

New cavers often wonder why a 3m climb is sometimes still referred to as the ‘Forty’ and a 6m ladder pitch is called the ‘Twenty’. Graham Mullan gives a brief explaination of two of the the puzzling names in Swildon's Hole.

The origin of the ‘Twenty’ is the easiest question to answer. It's roughly 20 feet deep, although in the interests of strict accuracy, it’s actually a bit shorter than that, but 20 is a nice round number and so the name stuck. It was first reached in 1914 but not passed until July 1921, seven years later.

The reason that the descent of the Twenty took so long was that there was a far more formidable obstacle further upstream - the ‘Forty’. Twice the depth and, for most of the time very, very wet. It’s difficult to appreciate now, but back in the early years of the 20th century the cave was much wetter and without modern caving gear exploaration presented a much more difficult challenge.

The problem of water was much reduced in the 1950s when the water company began abstracting from a source upstream of the entrance. Other factors, including changing weather patterns, have also contributed, to say nothing of the vast improvements in equipment and in clothing since the 1920s.

To see the Twenty as it is now, look at the photo on the right in the pair above in Stuart's trip write up. And for the now inaptly names Forty, look at the photo on the left with the caver standing only a few metres about floor level and read on to discover how it came to be like this ...

The ‘Forty’ was first reached in the 1900s. The approach to it is the Water Rift which in those days was tight, nasty and very wet. This ended in the Keyhole and climbing above that to ‘Suicides’ Leap’ enabled the impressive shaft to be reached. This was a serious obstacle and wasn’t successfully descended until August 1914, when the Twenty was first reached.

The Keyhole was widened quite soon after discovery and gave much easier access to the head of the pitch. This was a short distance below Suicides’ Leap and is the reason why the ‘Forty’ was only 35’!

As well as the weather, the minor matter of the First World War kept cavers somewhat preoccupied, and it wasn’t until the drought in the summer of 1921 that it was successfully passed once more and the Twenty passed for the first time.

More downstream exploration followed, but the Forty remained a serious obstacle and various attempts, some more successful than others, were made to divert the water away from people on the ladder. All this effort was rendered unnecessary in July 1968 when the Great Flood (a serious event, about which books have been written and TV documentaries made) completely altered the place. The bottom of the Water Rift had simply been filled with silt and sediment, held in place by a blockage near the bottom of the pitch. This was blasted out by the force of water leaving the gentle descent to the short climb down that we have today.

So when you next drop down through the hole at the bottom of the Water Rift and land in a tall, round chamber, look up and imagine what it would have been like climbing down a rope ladder wearing a tweed jacket and cap over ordinary trousers with nothing more than a candle to light your descent. Then imagine water pouring on your head at the same time and you might have some idea how the original explorers might have felt.

All this and much more can be found in the book 'Swildon’s Hole 100 years of Exploration' by Dave Irwin, Ali Moody and Andy Farrant.

Graham Mullan

The Hut in sunlight. Photo by Liz Green.

A huge thank you to Liz Green for all her work getting the area at the front of the Hut ready for the new term.

Liz kindly takes up her own petrol strimmer and works hard to get the grass down to a manageable level so cavers aren't plowing through wet grass up to their knees just to reach the sanctuary of the Hut.

Liz also keeps an eye on the place when cavers aren't in residence. So remember, there's actually no such thing as the hut fairy and that short grass is the result of several hours hard work by a UBSS member.

MUSEUM NEWS

Alex Drakopoulos working on the material from Wookey Hole. Photo by Graham Mullan.

There's been a lot going on in the museum in the past month as Museum Curator Linda Wilson reports ...

As part of the move towards museum accreditation, we’ve started using a new wizzy online cataloguing system for the collections, called eHive. It meets all the Arts Council standards that we need to work to and it’s also surprisingly straightforward to use.

There is now a link on the museum page of the website which leads to it.

As a proof of concept, Graham Mullan used it to input the details of a collection of 35mm slides by David Gilbertson, recently donated to the museum, which show aspects of the quaternary geology of Somerset. To see the material, go to the catalogue page and search for ‘Gilbertson’. We hope to have the slides scanned in the near future & will upload the scans to eHive, as well.

Graham has also embarked on a project to record the whereabouts of all the human material that has been recovered from Wookey Hole. There’s a lot of it and it’s in a lot of places. The UBSS museum has a collection retreived in the 1970s from Chamber Four and this seemed a good place to start. Graham has been working with Alex Drakopoulos from the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology Department at Bristol, who can both catalogue and identify the specimens. It seems that the original cataloguing carried out in the 1970s wasn’t great.

They are now about 25% of the way through the job, which seems like good progress. Work will continue and they have another volunteer joining them, too.

Meanwhile, I've been busy catching up on some long overdue admin dealing with some returned loans that have come back to us in the past year, both of which predate my time as curator by several decades! The easiest one to deal with was a small quantity of faunal material from Sun Hole in Cheddar Gorge that had been in the possession of the late Dr Roger Jacobi when he died and these ended up in the Natural History Museum along with a vast quantity of his own material. Eventually, it was noted that the catalogue numbers on the specimens did not match the NHM's system and this was traced to us and eventually returned 15 years after Roger's death, demonstrating the wisdom of direct marking on specimens where at all possible.

The second box was much larger, and contained material from Picken's Hole that had been in the possession of Kate Scott who worked on the faunal remains from the site. This came to light during an impending house move and was the subject of a great 'unboxing' video taken in the museum by Jess Brock and featured in our June newsletter. I knew I couldn't put this off any longer, so when I had a day put aside for a research visit by Owen Barnes-Noble of the University of Durham, I enlisted the help of a friend, Jo West, who had volunteered to help in the museum and we sat down with a copy of the site catalogue and many, many plastic finds bags of various sizes and started to excavate the layers in the box, neatly divided into layers corresponding to the archaeological layers in the dig, but divided up by tea towels, not earth. The layers mainly corresponded with layers 3 and 4, along with the some material from the transition between layers 3 and 4.

Jo West cradling a large box of newly bagged specimens from Picken's Hole. The reference M30 is the unique site identification number. Photo by Linda Wilson.

The box contained a lot of unidentified bone fragments, and these we bagged and labelled in their original groupings. This sort of material might look uninteresting, but now the Zooms technique (which stands of Zoo Archaeology by Mass Spectrometry) is able to take bone fragments and identify them down to species level. A lot of work has already been done on the bone scrap from Pickens by Professor Rhiannon Stevens of University College London, which results in boxes of scrap all coming back individually bagged and labelled after sampling, and yields a huge amount of information about the fauna at the site. And maybe one day she'll find the Neanderthal that the late Arthur ApSimon and I have always hoped for!

The specimens that did have a catalogue number were all entered into the catalogue showing they were present and correct that day, and where necessary they were given new boxes to expand the site archive. Checking the specimen numbers can be incredibly hard at times as they are written in incredibly small numbering in black ink, often needing multiple different magnifying instruments to be sure we had the right number.

A whole day passed in the blink of an eye and we had only reached the first tea towel divider! Meanwhile, Owen had been closely examining a flint from Aveline's Hole in the hope of identifying traces of ancient glue. Spoiler: he doesn't think he was successful, but the result of his investigation may well tell and interesting story as part of the history of our collection. More later when he's finished his analysis.

As I had another research visit the following week, Jo and I decided to finish our job then, as by the end of a long day we had teeny tiny numbers dancing in front of our eyes!

Our next researcher was Susan Walker from Warwick University who is working on the collection of Roman Coins from the Brean Down Roman Temple site excavated by Arthur ApSimon. Sue has visited before and, as ever, it was a pleasure to talk to her about the coins and to learn more about a small but important part of the UBSS collection.

Neat and tidy shelves! Photo by Linda Wilson.

While Susan was downstairs working on teeny tiny coins, Jo and I spent two full days upstairs excavating our way down through the last couple of layers in the large cardboard box, and it was with a great sense of satisfaction that we reached the end of our task and were then able to tidy up the shelves containing the Picken's material.

If you would like to get involved with the work of the UBSS museum, please let me know. There's always plenty of work to be done!

Linda Wilson

Alex Drakopoulos working on the material from Wookey Hole. Photo by Graham Mullan.

There's been a lot going on in the museum in the past month as Museum Curator Linda Wilson reports ...

As part of the move towards museum accreditation, we’ve started using a new wizzy online cataloguing system for the collections, called eHive. It meets all the Arts Council standards that we need to work to and it’s also surprisingly straightforward to use.

There is now a link on the museum page of the website which leads to it.

As a proof of concept, Graham Mullan used it to input the details of a collection of 35mm slides by David Gilbertson, recently donated to the museum, which show aspects of the quaternary geology of Somerset. To see the material, go to the catalogue page and search for ‘Gilbertson’. We hope to have the slides scanned in the near future & will upload the scans to eHive, as well.

Graham has also embarked on a project to record the whereabouts of all the human material that has been recovered from Wookey Hole. There’s a lot of it and it’s in a lot of places. The UBSS museum has a collection retreived in the 1970s from Chamber Four and this seemed a good place to start. Graham has been working with Alex Drakopoulos from the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology Department at Bristol, who can both catalogue and identify the specimens. It seems that the original cataloguing carried out in the 1970s wasn’t great.

They are now about 25% of the way through the job, which seems like good progress. Work will continue and they have another volunteer joining them, too.

Meanwhile, I've been busy catching up on some long overdue admin dealing with some returned loans that have come back to us in the past year, both of which predate my time as curator by several decades! The easiest one to deal with was a small quantity of faunal material from Sun Hole in Cheddar Gorge that had been in the possession of the late Dr Roger Jacobi when he died and these ended up in the Natural History Museum along with a vast quantity of his own material. Eventually, it was noted that the catalogue numbers on the specimens did not match the NHM's system and this was traced to us and eventually returned 15 years after Roger's death, demonstrating the wisdom of direct marking on specimens where at all possible.

The second box was much larger, and contained material from Picken's Hole that had been in the possession of Kate Scott who worked on the faunal remains from the site. This came to light during an impending house move and was the subject of a great 'unboxing' video taken in the museum by Jess Brock and featured in our June newsletter. I knew I couldn't put this off any longer, so when I had a day put aside for a research visit by Owen Barnes-Noble of the University of Durham, I enlisted the help of a friend, Jo West, who had volunteered to help in the museum and we sat down with a copy of the site catalogue and many, many plastic finds bags of various sizes and started to excavate the layers in the box, neatly divided into layers corresponding to the archaeological layers in the dig, but divided up by tea towels, not earth. The layers mainly corresponded with layers 3 and 4, along with the some material from the transition between layers 3 and 4.

Jo West cradling a large box of newly bagged specimens from Picken's Hole. The reference M30 is the unique site identification number. Photo by Linda Wilson.

The box contained a lot of unidentified bone fragments, and these we bagged and labelled in their original groupings. This sort of material might look uninteresting, but now the Zooms technique (which stands of Zoo Archaeology by Mass Spectrometry) is able to take bone fragments and identify them down to species level. A lot of work has already been done on the bone scrap from Pickens by Professor Rhiannon Stevens of University College London, which results in boxes of scrap all coming back individually bagged and labelled after sampling, and yields a huge amount of information about the fauna at the site. And maybe one day she'll find the Neanderthal that the late Arthur ApSimon and I have always hoped for!

The specimens that did have a catalogue number were all entered into the catalogue showing they were present and correct that day, and where necessary they were given new boxes to expand the site archive. Checking the specimen numbers can be incredibly hard at times as they are written in incredibly small numbering in black ink, often needing multiple different magnifying instruments to be sure we had the right number.

A whole day passed in the blink of an eye and we had only reached the first tea towel divider! Meanwhile, Owen had been closely examining a flint from Aveline's Hole in the hope of identifying traces of ancient glue. Spoiler: he doesn't think he was successful, but the result of his investigation may well tell and interesting story as part of the history of our collection. More later when he's finished his analysis.

As I had another research visit the following week, Jo and I decided to finish our job then, as by the end of a long day we had teeny tiny numbers dancing in front of our eyes!

Our next researcher was Susan Walker from Warwick University who is working on the collection of Roman Coins from the Brean Down Roman Temple site excavated by Arthur ApSimon. Sue has visited before and, as ever, it was a pleasure to talk to her about the coins and to learn more about a small but important part of the UBSS collection.

Neat and tidy shelves! Photo by Linda Wilson.

While Susan was downstairs working on teeny tiny coins, Jo and I spent two full days upstairs excavating our way down through the last couple of layers in the large cardboard box, and it was with a great sense of satisfaction that we reached the end of our task and were then able to tidy up the shelves containing the Picken's material.

If you would like to get involved with the work of the UBSS museum, please let me know. There's always plenty of work to be done!

Linda Wilson

DIGGING NIGHT AT GIBBETT'S BROW

Entrance shaft.

On the 15th of October, a group consisting of Kenneth McIver, James Smith, Mowgli Palmer and Ben Pett ventured into Gibbetts Brow Shaft on Mendip for a little light recreational digging. Ben describes their efforts …

On arrival it was clear that another group was already down there along with a coordinated system of digging and removal of the earth. The group was very friendly and left around the same time as we arrived.

Yes, it's a Mendip dig!

The first section of the cave includes a very long ladder, followed by a short crawl to another hole. A pulley system has been set up along this passage to allow easy removal of spoil. The next hole leads to the site of the dig. Once again there was a tight ladder down to the bottom where the digging was happening. Once we found a rhythm we got a good amount of excavation done and celebrated with a pint at the Hunters.

Entrance shaft.

On the 15th of October, a group consisting of Kenneth McIver, James Smith, Mowgli Palmer and Ben Pett ventured into Gibbetts Brow Shaft on Mendip for a little light recreational digging. Ben describes their efforts …

On arrival it was clear that another group was already down there along with a coordinated system of digging and removal of the earth. The group was very friendly and left around the same time as we arrived.

Yes, it's a Mendip dig!

The first section of the cave includes a very long ladder, followed by a short crawl to another hole. A pulley system has been set up along this passage to allow easy removal of spoil. The next hole leads to the site of the dig. Once again there was a tight ladder down to the bottom where the digging was happening. Once we found a rhythm we got a good amount of excavation done and celebrated with a pint at the Hunters.

Ben Pett

THE WAIT FOR CHEDDAR IS NEARLY OVER!

Thanks to the unrelenting efforts of Wayne Starsmore, CSCC's Conservation and Access Officer, an access agreement has finally been enterered into for some of the caves in Cheddar Gorge, namely Goughs Cave, Spider Hole and Reservoir Hole. UBSS has nominated Stuart Alldred and Jess Brock as our conservation wardens to lead trips on behalf of the club. Stuart recounts his first trip as part of the warden training ...

I can’t actually remember if I’ve ever visited Gough’s Show Cave as a tourist, or if I just remember helping to survey the Cheese Room many years ago. Either way, last Sunday I got to explore more of the cave in preparation for becoming a Cheddar warden for the club.

We met outside the entrance at 10am, and after some introductions (and a brief visit from Martin Grass, who thought I must be a student and was confused to learn I’m actually 39), we set off into the cave.

The first part of the training covered the areas used for adventure trips, and guidance on where we were and weren’t allowed to go. The second part involved learning the route to Lloyd Hall, which included a rather scenic 25m abseil down to a lake. The view from the top of the pitch was fantastic as I watched the person below slowly descend through the tube towards the black ripples of water! Sadly, I’d forgotten to bring a strap for my phone and didn’t trust myself not to drop it down the pitch and lose it in the lake. Something to remember for next time!

I still need to complete my training for Reservoir and Spider Hole, which I’m hoping to do by December. Once I’m certified, I’ll be available to lead trips.

Thanks to the unrelenting efforts of Wayne Starsmore, CSCC's Conservation and Access Officer, an access agreement has finally been enterered into for some of the caves in Cheddar Gorge, namely Goughs Cave, Spider Hole and Reservoir Hole. UBSS has nominated Stuart Alldred and Jess Brock as our conservation wardens to lead trips on behalf of the club. Stuart recounts his first trip as part of the warden training ...

I can’t actually remember if I’ve ever visited Gough’s Show Cave as a tourist, or if I just remember helping to survey the Cheese Room many years ago. Either way, last Sunday I got to explore more of the cave in preparation for becoming a Cheddar warden for the club.

We met outside the entrance at 10am, and after some introductions (and a brief visit from Martin Grass, who thought I must be a student and was confused to learn I’m actually 39), we set off into the cave.

The first part of the training covered the areas used for adventure trips, and guidance on where we were and weren’t allowed to go. The second part involved learning the route to Lloyd Hall, which included a rather scenic 25m abseil down to a lake. The view from the top of the pitch was fantastic as I watched the person below slowly descend through the tube towards the black ripples of water! Sadly, I’d forgotten to bring a strap for my phone and didn’t trust myself not to drop it down the pitch and lose it in the lake. Something to remember for next time!

I still need to complete my training for Reservoir and Spider Hole, which I’m hoping to do by December. Once I’m certified, I’ll be available to lead trips.

Stuart Alldred

INTO THE HELL HOLE ...

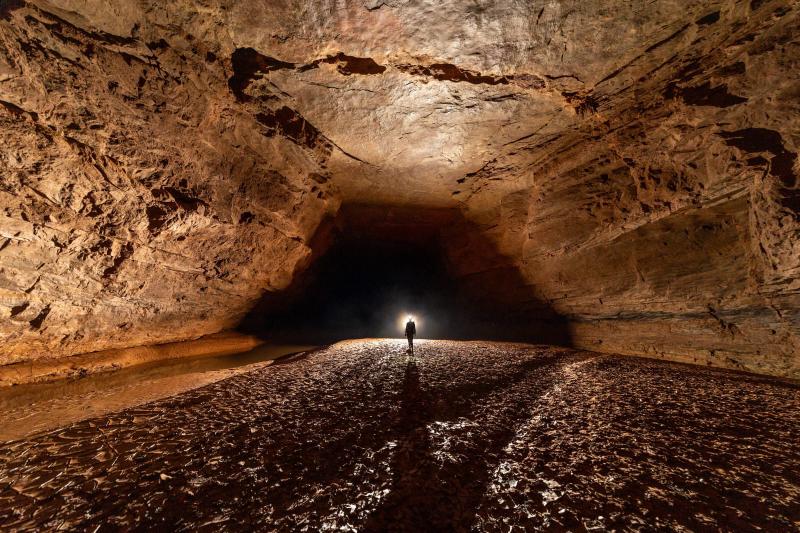

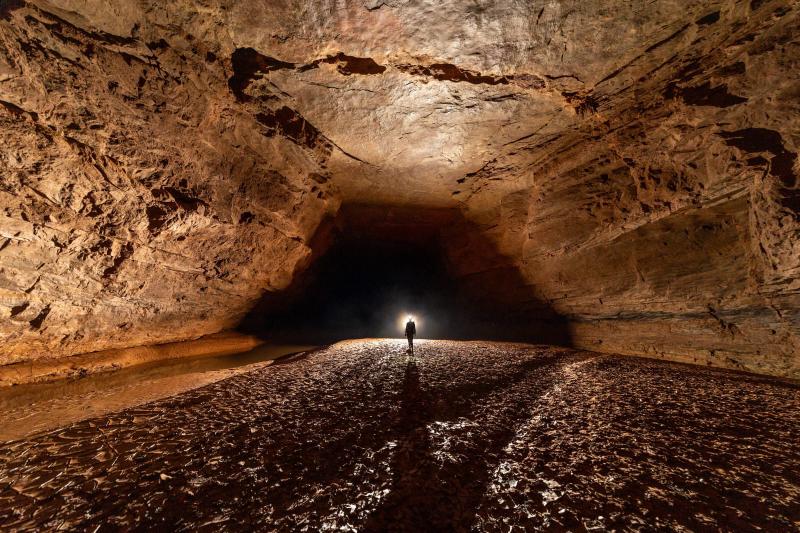

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Photo by Barkek Biela.

As mentioned in the last newsletter, Zac Woodford went the furthest afield this summer with a trip to Brazil for the 19th International Congress of Speleology. This is his account of a very impressive introduction to tropical caving in the ominously named Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério, which roughly translated means Hell Hole of the Cemetery Lagoon!

"No, I'm not sure I want to do this cave anymore," Paulina said, having suddenly stopped a few paces down the slope from me.

"Why?" I asked.

"When you get here you will see."

"Are there loads of spiders?" They were very much still on my mind, having only just, rapidly, come down the cobweb strewn entrance ladder.

"Just stand here and you will see."

I knew Paulina was joking, we'd come way too far to turn back at the entrance, but still, her trepidation was genuine.

She continued down the pallid flowstone slope and I followed after her. Right at the spot she had been standing, I realised why she had been so reticent to continue.

"Oh..." was all I could utter.

~~~~~

The cave entrance was at the bottom of a, by UK standards, HUGE sinkhole. The path to which was not nearly as wild as some of the others we'd take later in the week. Our guide, Lucas, stopped us just before we descended the rim to explain that there had once been a set of carved stairs down and that we would be, carefully, walking down what remained of them. Jussy, one of the local guides, also got Lucas to tell us to put our helmets on as he was concerned that the monkeys, if there were any about, may assault us with rocks… or worse.

The entrance hole was only one person wide and well hidden under the sinkhole cliff edge behind a house sized boulder. As we approached it we were warned to watch out for the Brown Recluse spider, which, if you were lucky, would only take off your arm.

Predictably, there was much faffing at the entrance as five photographers' worth of kit was passed down the rope ladder just inside. I was then last to enter the cave, taking extra care to watch where I was putting my hands. The ladder dropped out at the top of a calcite slope that I could already see led down to the lake. It was at that point in the trip when Paulina had her moment from the start of this story…

"Oh..." was all I could manage as what felt like a wall of hot custard hit me. I'm exceedingly familiar with the expression 'hot thick humid air' but you don't really internalise its meaning until it ambushes you like that. This was indeed going to be a 'sporting' cave.

I continued descending the slope to the shore line and realised just how different the scale of this cave was. It was titanic, almost literally, probably wide enough to admit that ill fated ship. The chamber was so enormous that I had to turn my torch up to full beam just to see the walls, which were at least 70m apart. And spanning the whole chamber, wall to wall, was the lake which disappeared around a corner some 150m ahead. What's more there were huge calcite formations in every corner and even rising up out of the lake. I had to just stand there, agape, to believe it.

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério - photo by Bartek Biela in collaboration with Kevin Downey.

While I was taking it all in, all about me a scene unfolded that would have been recognisable to anyone on the south coast of England in the months running up to June 6th 1944, only in microcosm. An amphibious landing was being prepared, albeit with the usual caver chaos and faff. Everyone had a life jacket and a car inner tyre which had to be inflated before the embarkation could begin. What few foot pumps we had were being passed around to inflate the inner tubes, which was a two person job as the pump-pipes needed to be held around the valve opening while the hard work was done.

Lucas had learnt from the previous day just how difficult having five photographers on a trip was going to be and so had set a rule: he was going to lead a group to the end of the cave and back, but on the way back, everyone had to leave with him. The local guides, Charles and Jussy would stay with the photography groups to keep them out of trouble.

I took off with the 'Speedy Team', which was most of the tour group, (minus Bartek and Kevin’s photography teams) into the lake. The crossing took a quarter of an hour being roughly 250m of swimming. It was also completely unlike UK cave water being a pleasant 24 degrees C. The landing was staggered by swimming speed, but once we were all across and had beached our inner-tubes we set off again.

Lago do Cruzeiro - Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lago do Cruzeiro - Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The landing site in question, and in fact the whole bank, was the base of a ginormous collapse pile that was covered in formations of all different kinds. At the top we could see huge globules of flowstone as we traced a path around the base that weaved between many stalagmites nicknamed 'candles' for their resemblance to melted wax. The far side of the pile transitioned from rubble to a large dry mud bank, from which we could look down at a vast muddy plain. Yes, a whole plain, inside a cave. Not a hundred meters from the bottom of the slope, we reached the banks of a river, and I do mean a river. Lucas explained that there were many resurgences inside the cave that formed tributaries that joined the main cave stream. We were now at the bank of one such tributary.

While the mud was dry elsewhere, surprisingly, in and around the river it wasn’t. This made the crossing difficult, as knee deep mud groped for everyone's wellies. I opted for the 'speed and power' approach, which was actually very successful - both at getting me across and getting me wet.

This set the pattern for much of the rest of the cave. There would be sections of walking interspersed with river crossings. Again, all in a truly vast passageway.

After another crossing, we came to the edge of a mud mountain which seemed to be the end of the cave. However, at floor height was an incredibly well decorated bedding plane out of which the river ran. Thus began one of only two sections of crawling. I chose the hands and knees crawl in the river, the water a welcome relief from the sweltering air. The other option was a flat out crawl on the bank (which I discovered was far less pleasant on the way out). The whole ceiling of the bedding plane was carpeted with stalactites and straws of various sizes.

On the far side, the cave changed character, the passageway becoming far smaller (but still HUGE by UK standards) and interspersed with car sized stal bosses that oozed down the walls. Also just on the other side of the bedding plane, we encountered another of the cave's features, and this one was quite large. Amblypygi, is the local name for them, although they're probably better known as Tailless Whip Scorpions. And once you get past how alien and terrifying they are, they’re actually quite cute. They are also completely benign, the worst they could do would be to give a nasty nip, but in my experience they always just ran away.

Cute? We'll take your word for it, Zac. Photo by Bartek Biela.

After some, brief, picture taking of Brazil's hottest new eight-legged model, we continued on. The river banks rose until the river was in a culvert several meters deep. Then we reached one of the greatest features in the cave - probably also one of the greatest in caving world wide - the mud slide. A 10m long steep-angled mud slide into the river. I waited in anticipation as I queued to go down, excited by the speed which the others were achieving. When my turn came the joy was all too short lived as I hit the water before I knew what was happening.

After climbing the opposing bank we stopped for lunch beside another calcite boss that looked like it had spilt all over the mud floor below. After lunch, and a 100-ish metres down the passage our group was thinned by several of the photographers peeling off to do their thing.

Eventually the passageway opened again and we had to make several more river crossings, including one at the base of a very steep mud bank. About at this point, we entered a truly VAST roundish chamber. The floor was covered in a layer of thin bits of breakdown but no huge boulders. Apparently in this chamber bits of dust regularly fall from the ceiling, which is directly below a regional main road.

Beyond the chamber, the passage narrowed and we had to make our way through a large area of breakdown. Part-way through this, Lucas stopped us as the now, very close, right-hand wall had become a flowstone slope where several more of our party turned back. Lucas instructed us to remove our muddy boots and then we then followed him up the slope. At that point, we saw a light catching up in the distance. We stopped and waited. Loz had finished with Bartek's photo-shoot at the entrance and had sprinted all the way to catch up with us!

At the top of the slope we met a series of person sized gour-pool terraces. The largest had a waterfall flowing into it, and on its edge was a flowstone encrusted Whip-Scorpion corpse. Lucas also drew our attention to the fact that, if you looked at the flowstone sparkles carefully, you could see that they were in fact rainbow coloured!

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Photo by Bartek Biela.

After this, the passage once again became truly vast with a flat mud floor. After another couple of river crossings, we reached the point where the cave changed most as Lucas led us into an opening in the left hand wall. The huge passage apparently continued for a while but the way to the very end was the person's width vadose canyon passage we were now following. This extended for 100m or so before it came out in the side of a larger sand-floored passage which we followed to the right.

The ceiling and floor began to get closer and closer until we reached the second crawl of the trip, which was mercifully soft and brief. At the end of this, we dropped into an even larger passageway and after only a few paces to the left, we reached the terminal upstream sump, and boy was it something to see…

A large pool occupied much of the low ceiling chamber but in the corner of this pool, and fueling it, was a large mushroom of water. The water pressure from up-stream was so great that as the water flowed out of its conduit it fountained out.

We stopped here for a while, having some snacks and enjoying the, relatively, cool waters before we turned back. The return was uneventful, albeit much quicker without Lucas’ period geology lectures (which I have omitted as this is a trip report, not a geology paper). The most eventful part was the backward lake crossing…

There I was serenely paddling along, Go-Pro in hand (or between my knees at least) when in the distance I saw Bartek approaching on his own small orange emergency inflatable raft (which he’d brought all the way from the UK). What’s more, he was doing so with some speed. As he got closer, I saw he was sitting, straddling the raft and clawing his way across the lake with a pair of dustpans, purchased from the supermarket that morning. One he was within 5m I could see the mad glint in his eye and I knew that he had no intention of stopping. WHAM! His raft collided with my inner tyre. The result was rather anticlimactic. We just kind of sat there for a moment before he overtook and paddled onwards.

Zac Woodford, not yet feeling deflated. Photo by Bartek Biela.

Back at the entrance shore, the others were given plenty of time to catch up as we cleaned (and deflated) our kit before heading out of the cave. Annoyingly the rope ladder had broken a rung, and the combination of that and the spiders made the 2m ascent rather more nerve racking than it should have been.

For my first experience of tropical caving, I would say I couldn’t have asked for better! A gentle introduction, not too big, not too arduous, not too many creepy crawlies. But bloody hot air, a bloody incredible lake and some bloody excellent formations. The one downside is that I know that it could be my only time going there, given the distance and cost associated with getting there but I very much hope this won't be the case as I would love to go back.

With thanks to the Tratman Fund of the University of Bristol and the Oliver Lloyd Memorial Fund for their support and to Bartek Biela for allowing me to use his photos.

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Photo by Barkek Biela.

As mentioned in the last newsletter, Zac Woodford went the furthest afield this summer with a trip to Brazil for the 19th International Congress of Speleology. This is his account of a very impressive introduction to tropical caving in the ominously named Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério, which roughly translated means Hell Hole of the Cemetery Lagoon!

"No, I'm not sure I want to do this cave anymore," Paulina said, having suddenly stopped a few paces down the slope from me.

"Why?" I asked.

"When you get here you will see."

"Are there loads of spiders?" They were very much still on my mind, having only just, rapidly, come down the cobweb strewn entrance ladder.

"Just stand here and you will see."

I knew Paulina was joking, we'd come way too far to turn back at the entrance, but still, her trepidation was genuine.

She continued down the pallid flowstone slope and I followed after her. Right at the spot she had been standing, I realised why she had been so reticent to continue.

"Oh..." was all I could utter.

~~~~~

The cave entrance was at the bottom of a, by UK standards, HUGE sinkhole. The path to which was not nearly as wild as some of the others we'd take later in the week. Our guide, Lucas, stopped us just before we descended the rim to explain that there had once been a set of carved stairs down and that we would be, carefully, walking down what remained of them. Jussy, one of the local guides, also got Lucas to tell us to put our helmets on as he was concerned that the monkeys, if there were any about, may assault us with rocks… or worse.

The entrance hole was only one person wide and well hidden under the sinkhole cliff edge behind a house sized boulder. As we approached it we were warned to watch out for the Brown Recluse spider, which, if you were lucky, would only take off your arm.

Predictably, there was much faffing at the entrance as five photographers' worth of kit was passed down the rope ladder just inside. I was then last to enter the cave, taking extra care to watch where I was putting my hands. The ladder dropped out at the top of a calcite slope that I could already see led down to the lake. It was at that point in the trip when Paulina had her moment from the start of this story…

"Oh..." was all I could manage as what felt like a wall of hot custard hit me. I'm exceedingly familiar with the expression 'hot thick humid air' but you don't really internalise its meaning until it ambushes you like that. This was indeed going to be a 'sporting' cave.

I continued descending the slope to the shore line and realised just how different the scale of this cave was. It was titanic, almost literally, probably wide enough to admit that ill fated ship. The chamber was so enormous that I had to turn my torch up to full beam just to see the walls, which were at least 70m apart. And spanning the whole chamber, wall to wall, was the lake which disappeared around a corner some 150m ahead. What's more there were huge calcite formations in every corner and even rising up out of the lake. I had to just stand there, agape, to believe it.

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério - photo by Bartek Biela in collaboration with Kevin Downey.

While I was taking it all in, all about me a scene unfolded that would have been recognisable to anyone on the south coast of England in the months running up to June 6th 1944, only in microcosm. An amphibious landing was being prepared, albeit with the usual caver chaos and faff. Everyone had a life jacket and a car inner tyre which had to be inflated before the embarkation could begin. What few foot pumps we had were being passed around to inflate the inner tubes, which was a two person job as the pump-pipes needed to be held around the valve opening while the hard work was done.

Lucas had learnt from the previous day just how difficult having five photographers on a trip was going to be and so had set a rule: he was going to lead a group to the end of the cave and back, but on the way back, everyone had to leave with him. The local guides, Charles and Jussy would stay with the photography groups to keep them out of trouble.

I took off with the 'Speedy Team', which was most of the tour group, (minus Bartek and Kevin’s photography teams) into the lake. The crossing took a quarter of an hour being roughly 250m of swimming. It was also completely unlike UK cave water being a pleasant 24 degrees C. The landing was staggered by swimming speed, but once we were all across and had beached our inner-tubes we set off again.

Lago do Cruzeiro - Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Lago do Cruzeiro - Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.The landing site in question, and in fact the whole bank, was the base of a ginormous collapse pile that was covered in formations of all different kinds. At the top we could see huge globules of flowstone as we traced a path around the base that weaved between many stalagmites nicknamed 'candles' for their resemblance to melted wax. The far side of the pile transitioned from rubble to a large dry mud bank, from which we could look down at a vast muddy plain. Yes, a whole plain, inside a cave. Not a hundred meters from the bottom of the slope, we reached the banks of a river, and I do mean a river. Lucas explained that there were many resurgences inside the cave that formed tributaries that joined the main cave stream. We were now at the bank of one such tributary.

While the mud was dry elsewhere, surprisingly, in and around the river it wasn’t. This made the crossing difficult, as knee deep mud groped for everyone's wellies. I opted for the 'speed and power' approach, which was actually very successful - both at getting me across and getting me wet.

This set the pattern for much of the rest of the cave. There would be sections of walking interspersed with river crossings. Again, all in a truly vast passageway.

After another crossing, we came to the edge of a mud mountain which seemed to be the end of the cave. However, at floor height was an incredibly well decorated bedding plane out of which the river ran. Thus began one of only two sections of crawling. I chose the hands and knees crawl in the river, the water a welcome relief from the sweltering air. The other option was a flat out crawl on the bank (which I discovered was far less pleasant on the way out). The whole ceiling of the bedding plane was carpeted with stalactites and straws of various sizes.

On the far side, the cave changed character, the passageway becoming far smaller (but still HUGE by UK standards) and interspersed with car sized stal bosses that oozed down the walls. Also just on the other side of the bedding plane, we encountered another of the cave's features, and this one was quite large. Amblypygi, is the local name for them, although they're probably better known as Tailless Whip Scorpions. And once you get past how alien and terrifying they are, they’re actually quite cute. They are also completely benign, the worst they could do would be to give a nasty nip, but in my experience they always just ran away.

Cute? We'll take your word for it, Zac. Photo by Bartek Biela.

After some, brief, picture taking of Brazil's hottest new eight-legged model, we continued on. The river banks rose until the river was in a culvert several meters deep. Then we reached one of the greatest features in the cave - probably also one of the greatest in caving world wide - the mud slide. A 10m long steep-angled mud slide into the river. I waited in anticipation as I queued to go down, excited by the speed which the others were achieving. When my turn came the joy was all too short lived as I hit the water before I knew what was happening.

After climbing the opposing bank we stopped for lunch beside another calcite boss that looked like it had spilt all over the mud floor below. After lunch, and a 100-ish metres down the passage our group was thinned by several of the photographers peeling off to do their thing.

Eventually the passageway opened again and we had to make several more river crossings, including one at the base of a very steep mud bank. About at this point, we entered a truly VAST roundish chamber. The floor was covered in a layer of thin bits of breakdown but no huge boulders. Apparently in this chamber bits of dust regularly fall from the ceiling, which is directly below a regional main road.

Beyond the chamber, the passage narrowed and we had to make our way through a large area of breakdown. Part-way through this, Lucas stopped us as the now, very close, right-hand wall had become a flowstone slope where several more of our party turned back. Lucas instructed us to remove our muddy boots and then we then followed him up the slope. At that point, we saw a light catching up in the distance. We stopped and waited. Loz had finished with Bartek's photo-shoot at the entrance and had sprinted all the way to catch up with us!

At the top of the slope we met a series of person sized gour-pool terraces. The largest had a waterfall flowing into it, and on its edge was a flowstone encrusted Whip-Scorpion corpse. Lucas also drew our attention to the fact that, if you looked at the flowstone sparkles carefully, you could see that they were in fact rainbow coloured!

Buraco do Inferno da Lagoa do Cemitério. Photo by Bartek Biela.

After this, the passage once again became truly vast with a flat mud floor. After another couple of river crossings, we reached the point where the cave changed most as Lucas led us into an opening in the left hand wall. The huge passage apparently continued for a while but the way to the very end was the person's width vadose canyon passage we were now following. This extended for 100m or so before it came out in the side of a larger sand-floored passage which we followed to the right.

The ceiling and floor began to get closer and closer until we reached the second crawl of the trip, which was mercifully soft and brief. At the end of this, we dropped into an even larger passageway and after only a few paces to the left, we reached the terminal upstream sump, and boy was it something to see…

A large pool occupied much of the low ceiling chamber but in the corner of this pool, and fueling it, was a large mushroom of water. The water pressure from up-stream was so great that as the water flowed out of its conduit it fountained out.

We stopped here for a while, having some snacks and enjoying the, relatively, cool waters before we turned back. The return was uneventful, albeit much quicker without Lucas’ period geology lectures (which I have omitted as this is a trip report, not a geology paper). The most eventful part was the backward lake crossing…

There I was serenely paddling along, Go-Pro in hand (or between my knees at least) when in the distance I saw Bartek approaching on his own small orange emergency inflatable raft (which he’d brought all the way from the UK). What’s more, he was doing so with some speed. As he got closer, I saw he was sitting, straddling the raft and clawing his way across the lake with a pair of dustpans, purchased from the supermarket that morning. One he was within 5m I could see the mad glint in his eye and I knew that he had no intention of stopping. WHAM! His raft collided with my inner tyre. The result was rather anticlimactic. We just kind of sat there for a moment before he overtook and paddled onwards.

Zac Woodford, not yet feeling deflated. Photo by Bartek Biela.

Back at the entrance shore, the others were given plenty of time to catch up as we cleaned (and deflated) our kit before heading out of the cave. Annoyingly the rope ladder had broken a rung, and the combination of that and the spiders made the 2m ascent rather more nerve racking than it should have been.

For my first experience of tropical caving, I would say I couldn’t have asked for better! A gentle introduction, not too big, not too arduous, not too many creepy crawlies. But bloody hot air, a bloody incredible lake and some bloody excellent formations. The one downside is that I know that it could be my only time going there, given the distance and cost associated with getting there but I very much hope this won't be the case as I would love to go back.

With thanks to the Tratman Fund of the University of Bristol and the Oliver Lloyd Memorial Fund for their support and to Bartek Biela for allowing me to use his photos.

Zac Woodford

A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

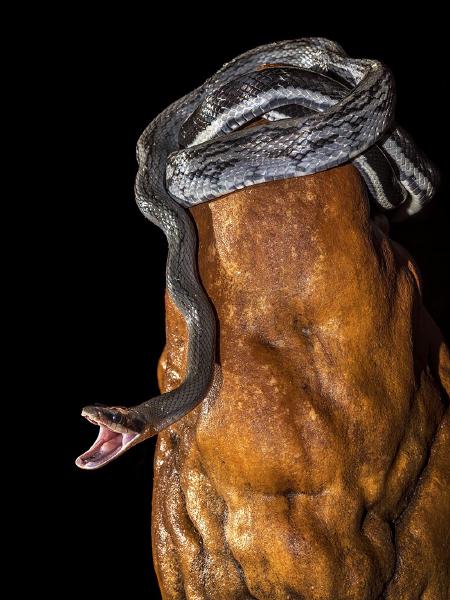

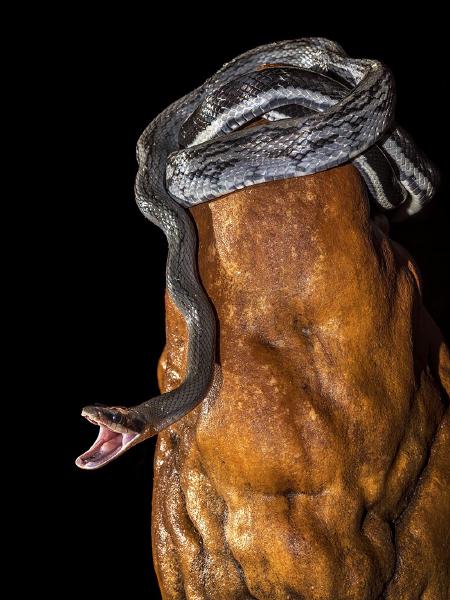

Cave racer snake in Snaketrack Cave, Mulu. Photograph by Chris Howes.

UBSS member Chris Howes has (again!) won some awards for his cave photography.

The image above shows a cave racer snake in Snaketrack Cave in Mulu, waiting on top of a stal to strike at a swiftlet or bat flying past, quite a distance into the cave. This won third place in the Life section at the International Congress of Speleology in Brazil.

Esztramos Cave, Hungary. Photo by Chris Howes.

Chris's photo of a caver on a ladder in Esztramos Cave in Hungary won second place in the general Caves section and also the second Sami Karkabi Photographic Award.

Sami Karkabi, who died in 2019 at the age of 86, did a huge amount of work for Lebanese caving and was closely associated with the exploration and development of Jeita Cave. He is credited with numerous scientific publications, both books and articles, as well as more than 25,000 cave photographs and 250,000 photos from his anthropological studies. This award in his memory is made by his caving club at each Congress.

Chris also gained first place in both the print category and the digital (projected image categories at Hidden Earth 2025.

You can learn more about Chris' photography and his many awards at his website.

Cave racer snake in Snaketrack Cave, Mulu. Photograph by Chris Howes.

UBSS member Chris Howes has (again!) won some awards for his cave photography.

The image above shows a cave racer snake in Snaketrack Cave in Mulu, waiting on top of a stal to strike at a swiftlet or bat flying past, quite a distance into the cave. This won third place in the Life section at the International Congress of Speleology in Brazil.

Esztramos Cave, Hungary. Photo by Chris Howes.

Chris's photo of a caver on a ladder in Esztramos Cave in Hungary won second place in the general Caves section and also the second Sami Karkabi Photographic Award.

Sami Karkabi, who died in 2019 at the age of 86, did a huge amount of work for Lebanese caving and was closely associated with the exploration and development of Jeita Cave. He is credited with numerous scientific publications, both books and articles, as well as more than 25,000 cave photographs and 250,000 photos from his anthropological studies. This award in his memory is made by his caving club at each Congress.

Chris also gained first place in both the print category and the digital (projected image categories at Hidden Earth 2025.

You can learn more about Chris' photography and his many awards at his website.

SCROTUM CLAMPERS AND WILD HEADS

Exit of the Petit Bidouze. Photograph by Lizzie Caisley (SWCC).

James Hallihan started his summer expo season with a trip to Austria (see his write up in the August newsletter) and then drove across Europe to reach the French side of the Pyrenees for the classic through trip of the Pierre Saint-Martin system. This is the story of both his epic drive there and the caving at the end of the journey.

After one last night with just five of us at basecamp in Austria, an early morning sweep and some last goodbyes, Muscy Hannah (an affectionate nickname due to the number of Hannahs and the fact this one is from Manchester (MUSC)), Hamish (also from MUSC) and I piled into my car and started driving towards the Pyrenees.